Down the Rabbit Hole - Part II: Analyzing an EFI Application with Radare2

After dumping my laptop's BIOS and extracting its UEFI modules, I searched for the relevant error string and found an efi application named LenovoWmaPolicyDxe.efi. It's time to analyze and understand this binary.

I've uploaded an untouched image carved from the official update iso from Lenovo's website. If you want to follow along you can download it from here.

In this post I will analyze the generic structures and functions of the EFI application with radare2. Since I also wanted to introduce radare2, I will have a beginner-friendly approach. I added an appendix to list the commands I used in radare2. In the next and final post I will analyze and modify/remove the whitelist mechanism itself.

Always be prepared

First of all, let me recap what I do know about this binary and what I expect to find inside:

- It's a (in my case x86-64) PE binary with little-endian encoding.

- EFI applications interface with each other through specified functions.

- The binary is probably statically linked and stripped.

- If I can resolve the interfaces and the services being used, I will be able understand what's going on.

Getting right into it

Opening the binary with r2 and analyzing with aaaaaa(one more 'a' and a radare2 developer will knock on my door, no need to bother them for now), then switching to visual mode, I get to see the entry of the application. Wasting no time, I find the offset of the error string and jump right to it.

:> izz

[Strings]

Num Paddr Vaddr Len Size Section Type String

000 0x000001c8 0x000001c8 5 6 () ascii .text

001 0x00000217 0x00000217 7 8 () ascii @.reloc

002 0x0000048a 0x0001048a 5 6 (.text) ascii '45_T

003 0x000004ae 0x000104ae 4 5 (.text) ascii *\n9\a

004 0x00000510 0x00010510 99 200 (.text) utf16le 1802: Unauthorized network card is plugged in - Power off and remove the miniPCI network card (%s).

005 0x000005d8 0x000105d8 4 5 (.text) ascii 1010

006 0x000005e0 0x000105e0 14 15 (.text) ascii KHOIHGIUCCHHII

007 0x000005f0 0x000105f0 19 40 (.text) utf16le %04x/%04x/%04x/%04x

008 0x00000618 0x00010618 9 20 (.text) utf16le %04x/%04x

...

[0x00010510 16% 2632 body.bin]> xc @ string

- offset - 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F 0123456789ABCDEF comment

0x00010510 3100 3800 3000 3200 3a00 2000 5500 6e00 1.8.0.2.:. .U.n.

0x00010520 6100 7500 7400 6800 6f00 7200 6900 7a00 a.u.t.h.o.r.i.z.

0x00010530 6500 6400 2000 6e00 6500 7400 7700 6f00 e.d. .n.e.t.w.o.

0x00010540 7200 6b00 2000 6300 6100 7200 6400 2000 r.k. .c.a.r.d. .

0x00010550 6900 7300 2000 7000 6c00 7500 6700 6700 i.s. .p.l.u.g.g.

0x00010560 6500 6400 2000 6900 6e00 2000 2d00 2000 e.d. .i.n. .-. .

0x00010570 5000 6f00 7700 6500 7200 2000 6f00 6600 P.o.w.e.r. .o.f.

0x00010580 6600 2000 6100 6e00 6400 2000 7200 6500 f. .a.n.d. .r.e.

0x00010590 6d00 6f00 7600 6500 2000 7400 6800 6500 m.o.v.e. .t.h.e.

0x000105a0 2000 6d00 6900 6e00 6900 5000 4300 4900 .m.i.n.i.P.C.I.

0x000105b0 2000 6e00 6500 7400 7700 6f00 7200 6b00 .n.e.t.w.o.r.k.

0x000105c0 2000 6300 6100 7200 6400 2000 2800 2500 .c.a.r.d. .(.%.

0x000105d0 7300 2900 2e00 0000 3130 3130 0000 0000 s.).....1010....

First thing to do is to check where this string is being referenced in the code. Checking the xref results in a surprise:

[addr.xrefs]> 0x0000000000010510 # (TAB/jk/q/?)

(no xrefs)

*sigh* That's just great. I have a string that isn't referenced in any part of the program. Now what do I do?

A little detour

I literally had nightmares about this string after not being able to find any xrefs. At this point my dreams were crushed. Not knowing what to do, I will start analyzing the functions one by one to see if anything comes up. Fortunately there aren't many functions to look at, so that's something. Let me show you how the function list looks before analysis:

:> afl

0x00010960 4 156 fcn.00010960

0x000109fc 6 276 fcn.000109fc

0x00010b10 40 764 fcn.00010b10

0x0001101c 6 268 entry0

0x00011128 3 24 fcn.00011128

0x00011140 1 43 fcn.00011140

0x0001116c 3 63 fcn.0001116c

0x000111ac 1 182 fcn.000111ac

0x00011264 87 988 fcn.00011264

0x00011640 1 29 fcn.00011640

0x00011660 61 763 fcn.00011660

0x00011960 1 67 fcn.00011960

0x000119a4 1 32 fcn.000119a4

0x000119c4 12 241 fcn.000119c4

0x00011ab8 23 385 fcn.00011ab8

0x00011c3c 1 10 fcn.00011c3c

0x00011c48 3 28 fcn.00011c48

0x00011c64 8 60 fcn.00011c64

0x00011ca0 4 17 fcn.00011ca0

Analyzing these functions will hopefully help me uncover some of the mysteries of EFI applications. I will begin with the most obvious function since I do not yet know where to go.

Entry function

Any variable that's used in the entry0 function will probably be useful later. Before anything else, I need to know about the calling convention used in this type of binaries.

Calling convention in EFI applications

From the latest UEFI Specification document:

The calling convention is specified for each architecture. Specification for x64 systems is:

I also looked for EFI application development tutorials. The simplest EFI application looks like this:

#include <efi.h>

EFI_STATUS main(EFI_HANDLE ImageHandle, EFI_SYSTEM_TABLE *SystemTable)

{

return EFI_SUCCESS;

}

Now I need to import these types into r2. However around the time I was writing this piece, r2 was actually not able to parse behemoth.h(which is the best option to get every type at once) from ida-efiutils, but got an update that fixed the issue. Although, it's still not able to fully parse it because of its humongous size, so I had to cut out a big (hopefully not necessary) chunk of it. You can find the file in this gist. Anyway, this is still better than handcrafting a custom header file.

Now I can go through the function.

Unfortunately, r2 guessed the function arguments incorrectly (Hopefully it will improve in the future). The function fcn.000119a4 is called immediately, which means that arguments ImageHandle and SystemTable are passed to it. Let me quickly take a look:

This function is a pretty small and straightforward one. It takes the SystemTable and extracts two pointers and puts them into somewhere in memory. I will rename this function to InitTable and mark these offsets accordingly.

SystemTable goes into 0x11d98, and (using the offsets in this file) the variable at offsets:

- 0x60 is

EFI_BOOT_SERVICES *BootServices - 0x58 is

EFI_RUNTIME_SERVICES *RuntimeServices

Back to entry0. After naming these memory offsets, I saw that the function at SystemTable.BootServices+0x140, which points to LocateProtocol function, is called four times.

If any of these blocks fail, the program exits with a negative value.

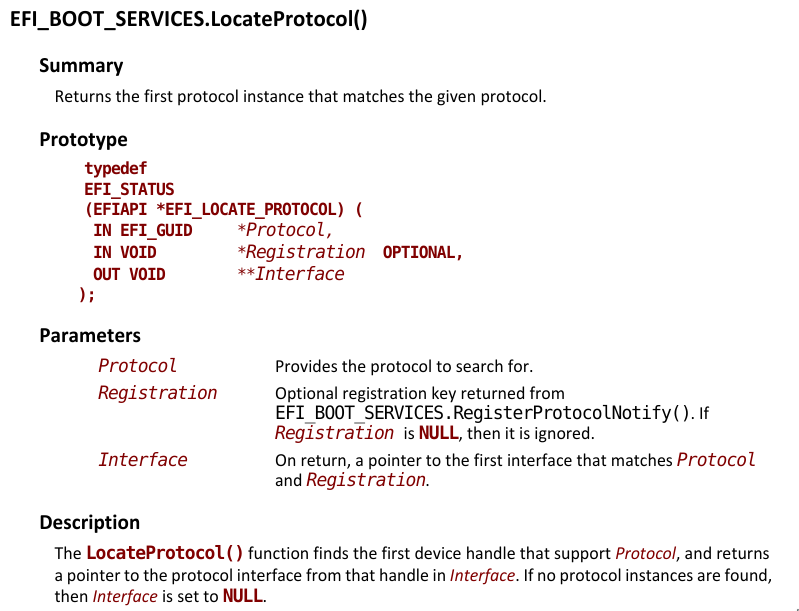

LocateProtocol function

This means that RCX will hold the pointer to GUID for the protocol and R8 will hold the memory address that will keep the interface. To name these memory addresses, I need to know what protocol is being called. In UEFI, protocols are registered with GUIDs. First I need to know how GUIDs are kept in memory, then I will try to resolve them.

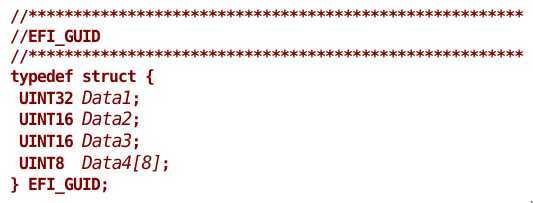

GUID struct

GUIDs are stored in the following struct:

To see the bytes in the correct order, I use formatted print:

:> pfq x[2]w[8]b

0x03583ff6

[ 0xcb36, 0x4940 ]

[ 0x94, 0x7e, 0xb9, 0xb3, 0x9f, 0x4a, 0xfa, 0xf7 ]

Which corresponds to the GUID 03583FF6-CB36-4940-947E-B9B34AFAF7. When I searched for this GUID in the UEFI dump, nothing showed up. I found a GUID dump and found that this GUID belongs to EfiSmbiosProtocol. I wasn't this lucky with all of the GUIDs. I failed to resolved the second and the third. Here's the table so far:

03583FF6-CB36-4940-947E-B9B39F4AFAF7 EfiSmbiosProtocol

3161DDAB-9600-4301-AAB2-93006395824A UnknownProtocol1

44029FA7-AB98-4506-966C-32D2DEEB2A0A UnknownProtocol2

E6F014AB-CB0E-456E-8AF7-7221EDB702F7 TpAcpiNvs

Right after four LocateProtocol blocks, the last block of entry0 is executed:

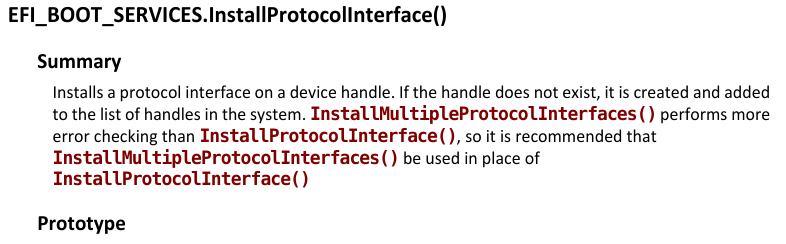

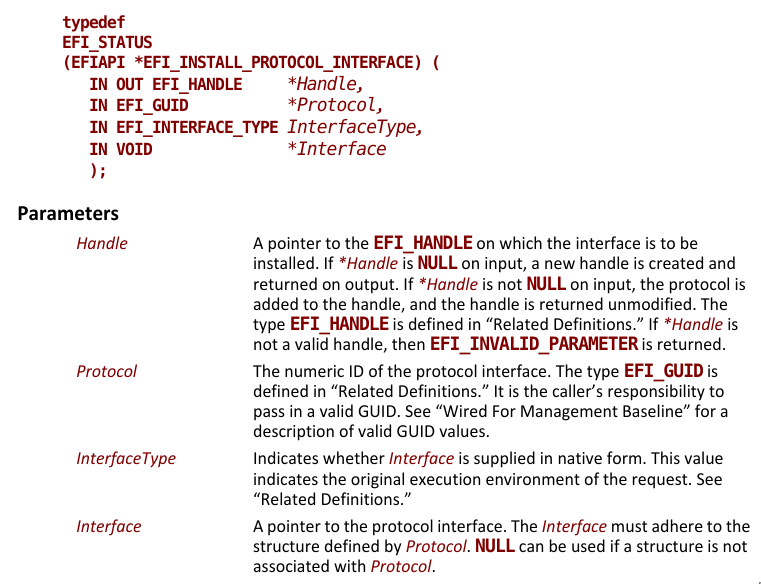

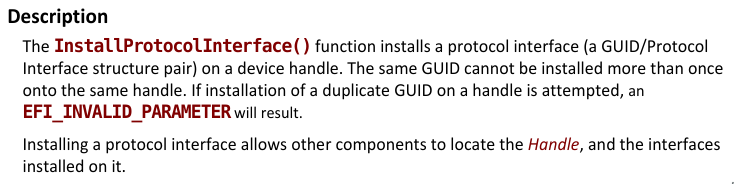

First of all, I want to know the call being made. BootServices+0x80 points to the InstallProtocolInterface function.

InstallProtocolInterface function

So here's what is happening:

- A new interface is being installed into

TpAcpiNvshandle. - The function at

0x10e0c(which isn't in the function list that was generated after the analysis) is being used for this protocol. I will name the functionInterfaceFunction. - This protocol has the GUID

4212A9D4-4A92-4BFB-B47F-2734355F54AC(Searching for this GUID yields references inLenowoWmaUsbDxe.efiandLenovoWmaPciDxe.efi)

I named the handle SelfHandle. After the call to InstallProtocol, the handle is put into 0x11d88, fcn.00011960 is called with the arguments (0x10, fcn.00010fc4, 0, &var_20h) and then rax is set to 0 and the program returns.

Now, at this point I have three unknown functions, two unknown protocols and no xref to my string. I will continue with fcn.00011960.

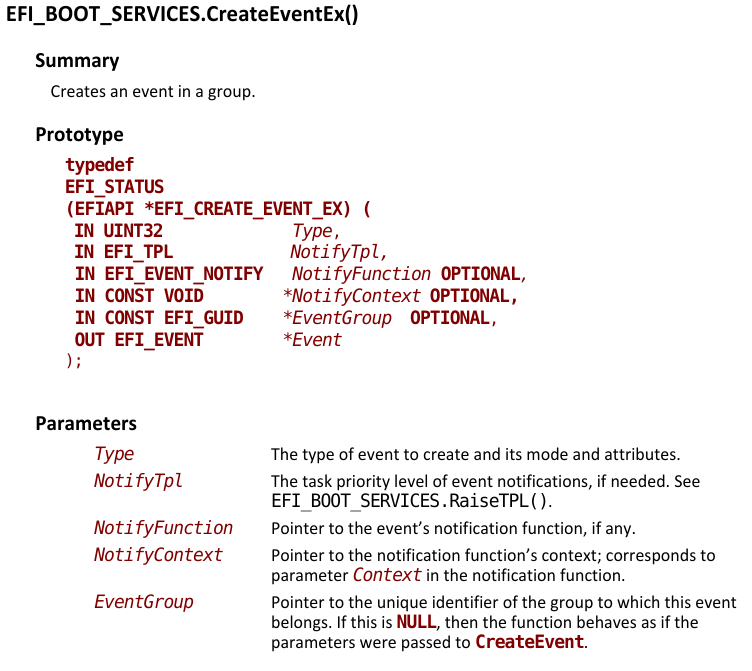

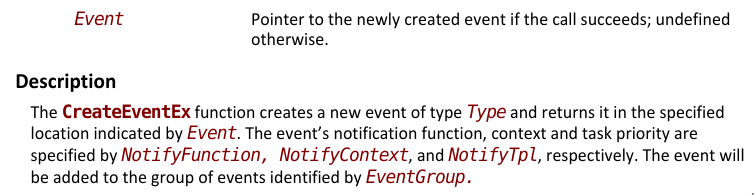

BootServices+0x170 is the CreateEventEx function:

CreateEventEx Function

In fcn.00011960 this function is called with the arguments (0x200, 0x10, fcn.00010fc4, 0, 0x10470, &var_20h). fcn.00010fc4 uses the UnknownProtocol1, so I do not know what it actually does. I will rename fcn.00011960 to CreateEventFunction and fcn.00010fc4 to UnknownProtocol1Function.

I honestly have no idea what this event does, so I will skip it for now and carry on to the InterfaceFunction, but first I want to find the standard functions such as printf, strcpy, memcpy and so on as these functions will help me understand what is going on more easily.

Standard functions

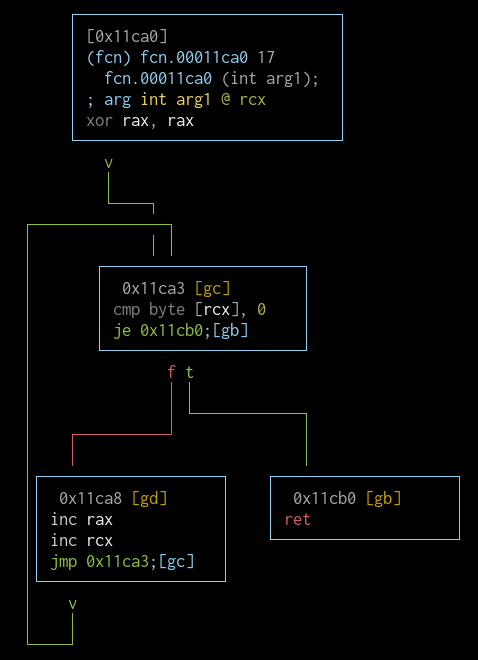

fcn.00011ca0 (strlen)

Well, this one looks pretty straighforward. Counting bytes until the byte is equal to zero sounds like strlen().

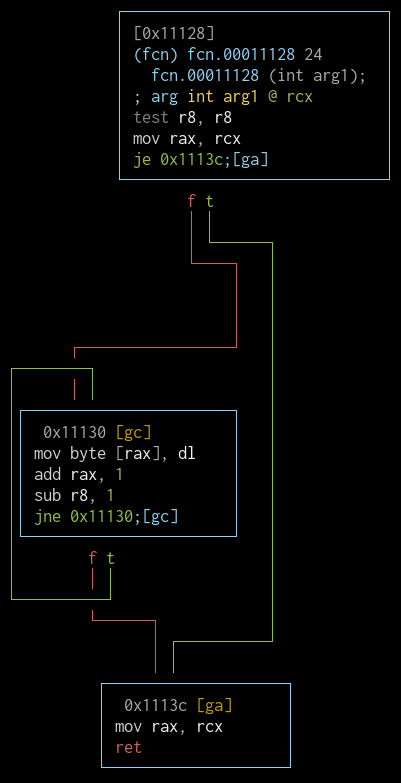

fcn.00011128 (memset)

This one looks like memset().

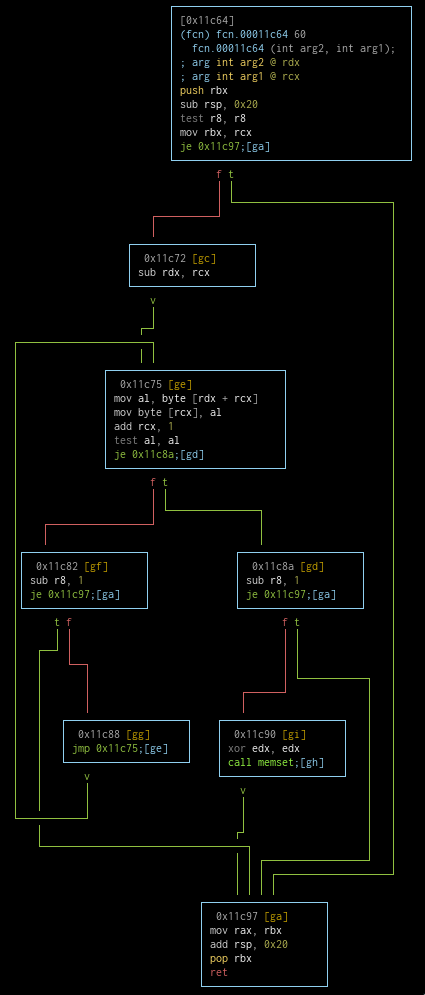

fcn.00011c64 (strncpy)

Copying bytes from the address in rdx to the address in rcx, while checking for a null byte, then using memset() on the remaining bytes is exactly what happens when strncpy() is called.

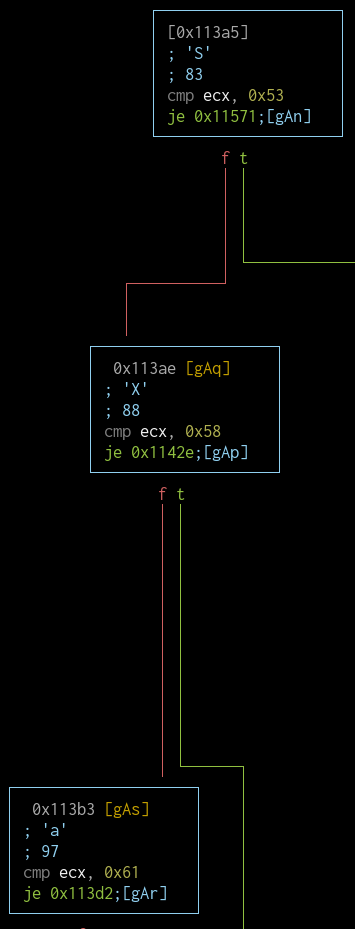

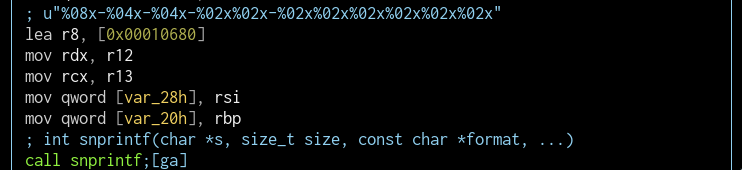

fcn.00011264 (vsnprintf)

This is one big function, however something as little as these lines give it away immediately:

These look like format string operators! I assume that I'm looking at a printf function. This function only has one xref (fcn.00011640) and that function looks like a wrapper function.

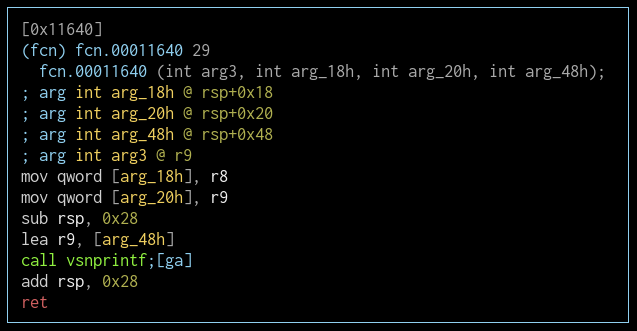

fcn.00011640 (snprintf)

Judging by the arguments it's called with in xrefs, this function might be snprintf(). This makes me think that the previous function is probably vsnprintf().

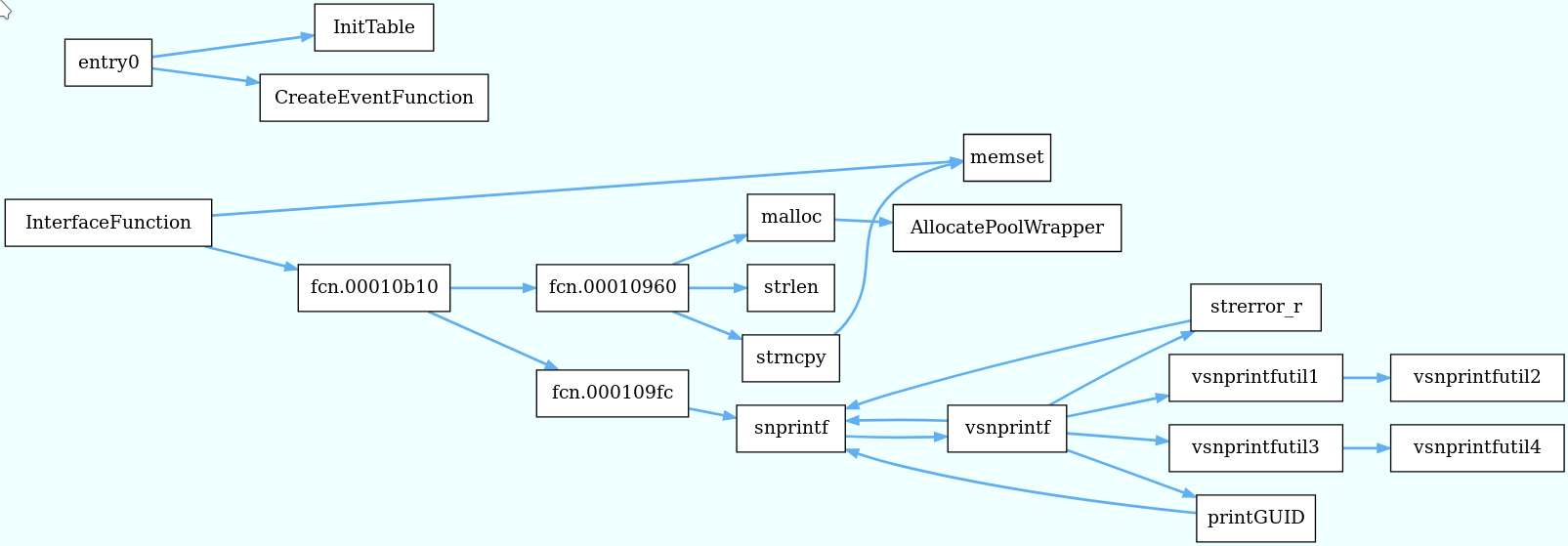

Looking at the global call graph, there are several functions that are only invoked in vsnprintf. I will rename them and analyze them later when it's absolutely necessary. However there are two functions that call snprintf. I feel like I should take a look at them.

fcn.000111ac (printGUID)

The string gives this function away. This one must be a GUID print function.

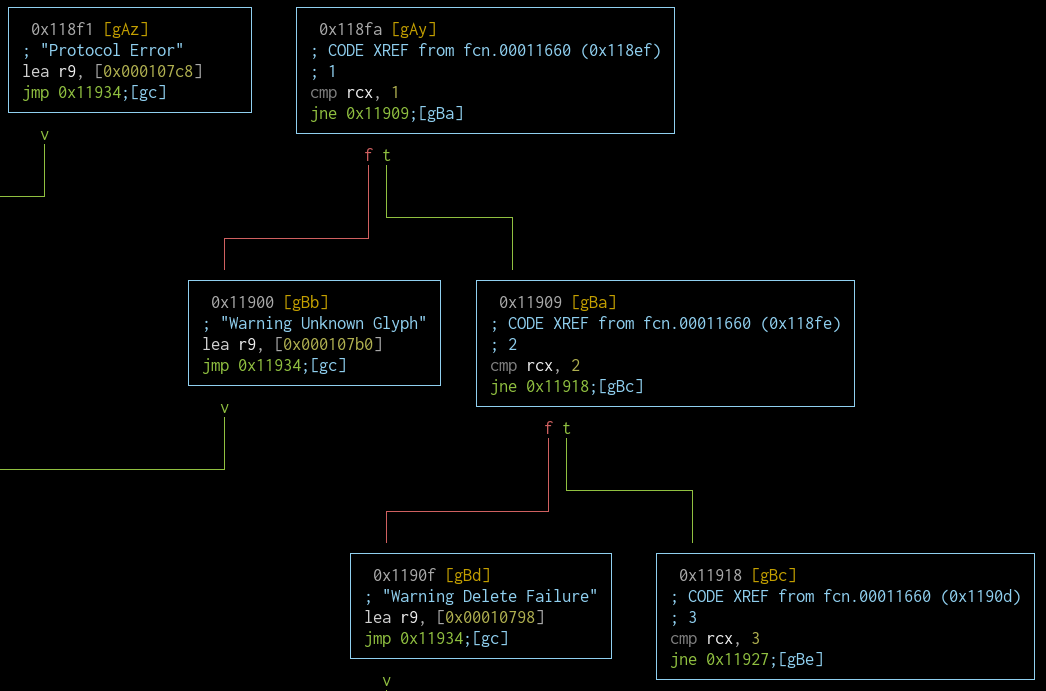

fcn.00011660 (strerror_r)

I've got lots of error codes and strings. It looks like this function prints the error string to the given buffer based on the status code. This function is probably a custom strerror_r().

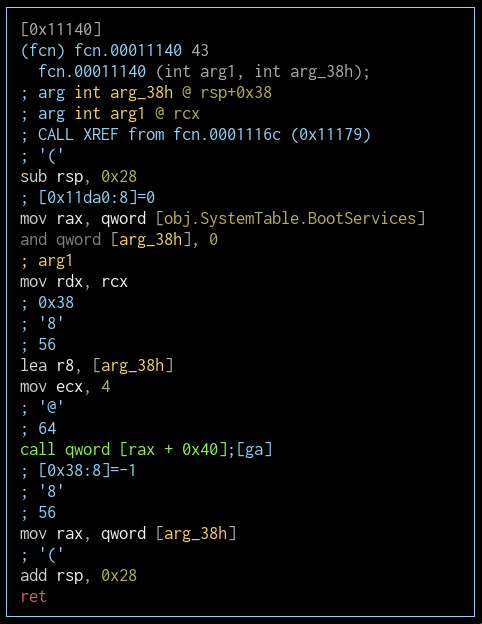

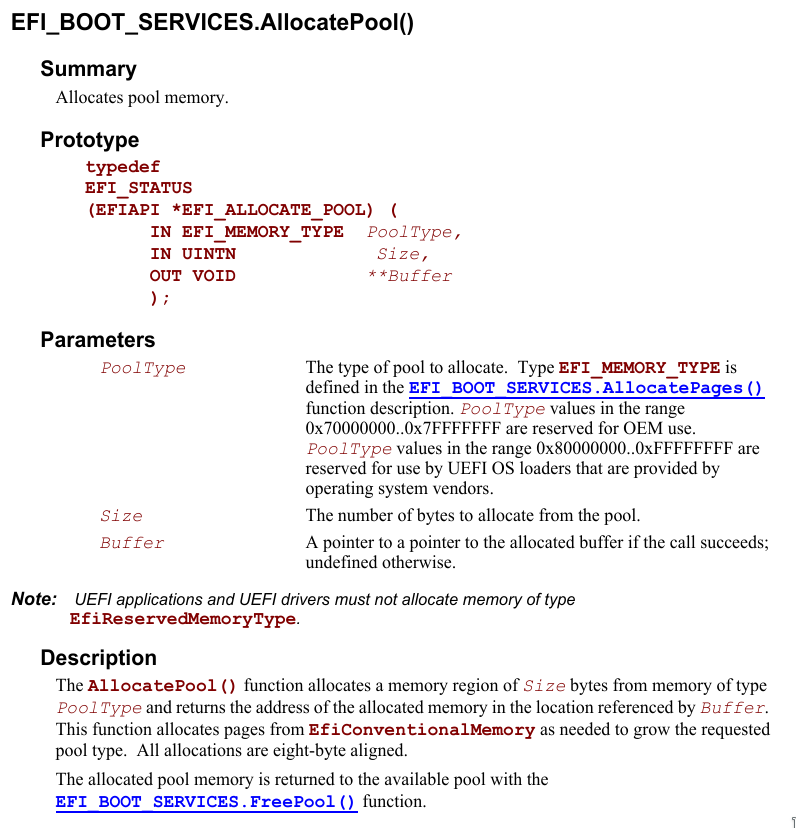

fcn.00011140 (AllocatePoolWrapper)

BootService+0x40 (which is AllocatePool) is called in this function.

AllocatePool function

This is basically a syscall for allocating memory. I will name this one AllocatePoolWrapper and look at the calling function.

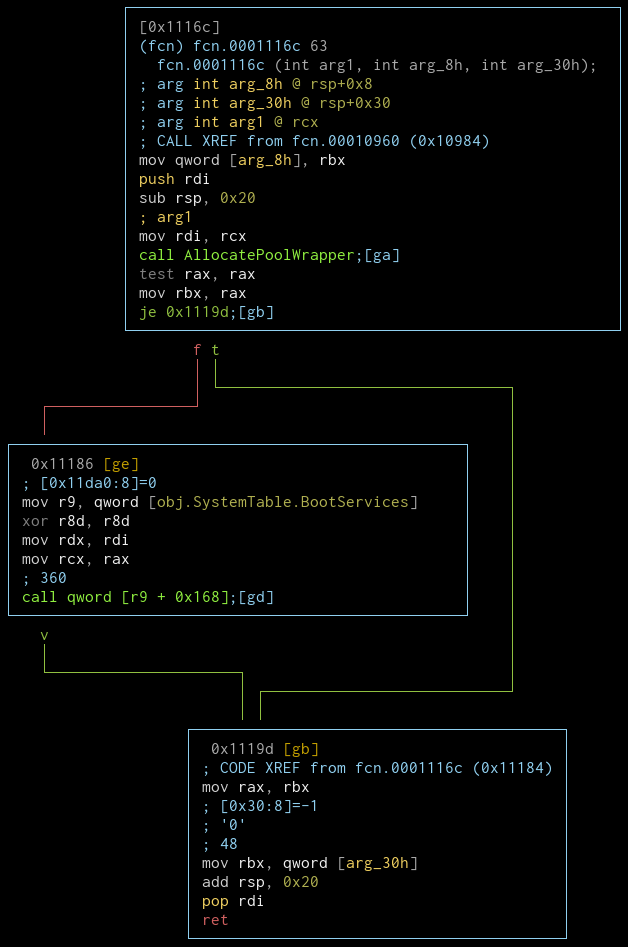

fcn.0001116c (malloc)

If the AllocatePoolWrapper succeeds and returns a buffer, the buffer is initialized to \x00 by the BootServices+0x168 which is SetMem. This function looks a lot like malloc().

A step in the right direction

The function list now looks like this:

:> afl

0x00010960 4 156 fcn.00010960

0x000109fc 6 276 fcn.000109fc

0x00010b10 40 764 fcn.00010b10

0x00010e0c 19 440 InterfaceFunction

0x00010fc4 8 85 UnknownProtocol1Function

0x0001101c 6 268 entry0

0x00011128 3 24 memset

0x00011140 1 43 AllocatePoolWrapper

0x0001116c 3 63 malloc

0x000111ac 1 182 printGUID

0x00011264 87 988 vsnprintf

0x00011640 1 29 snprintf

0x00011660 61 763 strerror_r

0x0001195c 1 3 EmptyFunction

0x00011960 1 67 CreateEventFunction

0x000119a4 1 32 InitTable

0x000119c4 12 241 vsnprintfutil1

0x00011ab8 23 385 vsnprintfutil3

0x00011c3c 1 10 vsnprintfutil2

0x00011c48 3 28 vsnprintfutil4

0x00011c64 8 60 strncpy

0x00011ca0 4 17 strlen

Also my callgraph looks like this:

I analyzed and resolved most of the infrastructure. Then suddenly I had a thought:

What if the error string's offset is saved somewhere in the memory and used as a reference?

The string is stored at 0x10510. Its absolute offset from the beginning of the binary is 0x510. When I searched for \x10\x05 something came up:

:> /x 1005

Searching 2 bytes in [0x11ea0-0x11ec0]

hits: 0

Searching 2 bytes in [0x11de0-0x11ea0]

hits: 0

Searching 2 bytes in [0x10240-0x11de0]

hits: 1

0x00010258 hit1_0 1005

And when I checked the xrefs for that address:

:> axt @hit1_0

fcn.000109fc 0x10a8e [DATA] mov r8, qword [0x00010258]

Bingo. My error string is being referenced by a reference in fcn.000109fc. In the next and final post I will quicky analyze the remaining four unknown functions and see how I can get rid of the whitelist once and for all.

cya on the next one.

Appendix: Radare2 usage in detail

Note: Always use the git version of radare2. It's constantly updated and fixed so you might get a fix or a feature you didn't even know you needed.

Starting r2

Opening a binary(or any file) is as easy as:

$ r2 body.bin

This will spawn r2's shell. From here on it is r2 territory.

Analysis

Analysis happens on various levels. The simplest analysis can be run by typing:

[0x0001101c]> aa

[x] Analyze all flags starting with sym. and entry0 (aa)

It is possible to run more in-depth analysis by increasing the number of a's.

[0x0001101c]> aaaaaa

[x] Analyze all flags starting with sym. and entry0 (aa)

[x] Analyze function calls (aac)

[x] Analyze len bytes of instructions for references (aar)

[x] Constructing a function name for fcn.* and sym.func.* functions (aan)

[x] Enable constraint types analysis for variables

Visual mode

To switch to r2's visual mode simply type V in the shell (If you want to jump to the function callgraph directly, type VV). There are several viewmodes in visual mode, two of which are hexdump mode and the dissassembly mode. To rotate view modes, p/P can be used. The shell can be invoked with : when you're in visual mode. The rest of the commands can be listed with ?.

Strings

Strings can be listed with iz (for data sections) and izz (for the whole binary). This list can be grepped inside r2 shell. Strings can also be searched directly with / foo (ASCII) and /w foo (wide strings). After the search, r2 will create flags like hit0_1 on the matching offsets so that you can easily access them.

Jumping around

Changing the offset is done with the s command in the shell. In visual mode, o will allow you to jump to both addresses and flags and _ will list the available flags, allowing search.

References

Reference commands are under ax. You can list reference-related commands with ax? (Any command and its extensions can be listed with adding a question mark at the end). References to flags can be listed with axF and references to addresses can be listed with axt. In visual mode you can list the xrefs to the current offset with x.

Functions

Functions can be listed with afl. For a more verbose output, afll can be used. In visual mode, v opens the functions/variables analysis menu.

Types

Type commands are under t. To list loaded basic types use t, for loaded structs use ts and for typedefs use tt. To import types from a C header file, use to <path>. If you want to enter a type by hand, use to -. This command will spawn the editor registered in cfg.editor (this can be changed with e cfg.editor=<editor>). Function argument/variable types can be changed using afvt [name] [type].

Function arguments and variables

Function arguments and variables are manipulated through afv? commands. To rename vars use afvn [newname] [oldname]. You can remove vars with afv- [name].

Creating and renaming flags

Flags of any kind can be created with f [name] @[address]. To remove a flag use f- [name] or f- @[address]. In visual mode you can use d to define a flag at the current offset. You can also use b or _ to browse flags.

Callgraphs

Graphs are generated with ag? commands. For example, interactive ascii art of global callgraph can be generated with agCv and graphviz dot model of global callgraph can be generated with agCd (which is what I used for the graph in this post).